(Contains no spoilers!)

(*I can’t seem to apply italics to the book title in the heading.)

I did consider whether I should venture into fiction developmental editing, but I decided that for as long as I’ve got both textbook and journal paper editing on the go, I probably shouldn’t try to diversify any further. That said, if anybody would like me to beta read your fiction manuscript, I would be happy to do that and to provide a high-level review, such as I provide in this post. You are welcome to reach out to me via the Contact tab on this site.

Well, I fancied a bash at reviewing a work of fiction for a change, and here we go.

I chose Daughters of Night written by Laura Shepherd-Robinson because: one, it’s the most recent book I have read; and two, I used to be acquainted with the author, and as I always thought she was destined to be a writer, I am curious to read her work.

Daughters of Night is a sequel of sorts to Shepherd-Robinson’s first book, Blood & Sugar, which I’ve also read. You don’t necessarily need to have read the first book to enjoy the second. Both feature the characters of Caro(line) Corsham and Peregrine Child, with the same setting of late eighteenth-century London.

If it’s possible to give this book a short synopsis, it would run something like this: Caro Corsham, a well-to-do woman whose husband (the central character of Blood & Sugar) is away overseas, becomes hell-bent on finding a prostitute’s murderer. She enlists the help of Peregrine Child, and they both follow various leads to solve the murder. The story encompasses key character groups of a money lender and his indebted, a painter and his cold-hearted wife, government officials, and plenty of harlots.

The book is not (always) an easy read, and it’s not going to suit everyone. However, maybe it’s best to start with looking at its strengths.

There has clearly been a lot of research into the time period and the contexts surrounding the characters, and this would delight historians. We have details bridging the English colonies in the Americas to the glasshouse-grown pineapple trade to antiquity to games of the period. Eighteenth-century London also isn’t perhaps an obvious backdrop for contemporary fiction, and I’m sure there are not many authors who could manage to bring the period to life with an accessible storyline very convincingly.

Another strength is that there are a couple of really well-crafted plot twists. You have to wait until you get to these, but they are quality twists.

Now, onto the (contestably) weaker points. These are discussed by sub-points.

Length needs trimming

A key issue with this book seems to be its length. Perusing Amazon and Goodreads reviews, many commentators remark that the book is too long. The hardback edition is over 550 pages long (I won’t expand on how it’s uncomfortable to hold up when reading in bed—perhaps the e-book format is advised here).

For readers who like to be drawn into a labyrinth and held there, the length may not present any complaints. However, while there is some impressive attention to detail and the start to finish does all hang together, the story doesn’t become a page-turner until you approach the last hundred pages or so. That means for the first three hundred pages, there can sometimes be a sense of sticking with things and appreciating the detailing rather than feeling a punch factor that leaves you reeling and wanting more.

I do think that this story could have been shortened by at least fifty pages. Ideally more like a hundred. This could have primarily been achieved by cutting back on some of the meetings and conversations in the earlier stages of the murder investigation. Similar to Blood & Sugar, before the ‘page-turner stage’, there are simply so many brief meetings that provide very little substance or real clues to build real intrigue or to genuinely push the story forward. Exactly as Blood & Sugar, the in-the-dark stage of the plot is overly prolonged. The number of meetings should have been reduced, and redundant meetings should have been cut. For example, there is one meeting between Corsham and government officials mid-way through that feels completely disposable as far as plot progression is concerned. Added to that, there are a number of sub-narratives, a couple of which could have been dropped in my view.

For an author, it can be hard to let go of some things that have been so carefully researched and which seem like clever ideas, but too many garden paths will certainly cost five-star reviews. It is not an editor’s job to decide on the exact cuts, but a good editor will point out areas that are constricting the pace.

Questionable character attributes

Another common criticism of many of the Amazon and Goodreads reviews that I’d tend to agree with is that you don’t feel heavily invested in the two main characters of Corsham and Child. If you look at many good novels, main characters often carry plenty of flaws to the extent that they can even be repulsive, but in Daughters of Night, the main characters of Corsham and (especially) Child often feel little more than mechanical vehicles whose sole role is to line up the next interviewee until it’s time for a rapid succession of putting two and two together at the end. Their own stories are not the stories that interest us most. Corsham does have a sub-plot around her role as a mother, but despite the ‘infant factor’, whether she or Child live or die in this story—or even get physically hurt, which they do (multiple times)—isn’t going to shake the reader to the core. You know, though, that it’d be unlikely that Corsham would be killed off before the end, since to lose the one who’s most vested in finding the killer would leave us with none of the other characters sharing the same impetus to resolve the story. However, killing off Corsham could have provided an extra twist at the end, and the voice of one of the dead characters could have taken over at that point. (Except that would leave unresolved what happens to Corsham’s baby, which I suspect we’ll be finding out about in Shepherd-Robinson’s next novel.)

As for Child, he seems to need to be in the story because provides support and a sounding board for Corsham’s quest for truth. But we end up having two characters who are sometimes pursuing the same line of enquiry with the same people, which also adds to the sense of unnecessary protraction of the story. I’m not fully convinced as to Child’s purpose in the story, and in some ways his shoes could have been better filled by one of the Black characters from Blood & Sugar (Black people were noticeably nowhere to be seen in Daughters of Night). I think I went through the whole story with little visualization evoked as to what Child even looked like as a person. His actions suggest he is a rough figure, but on the other hand he has been married and a father.

Another issue with Corsham and Child is that they sometimes possess superhuman-like strength. Particularly with Child, you sometimes feel like he’s being thrust into adventure game scenes, and that he’ll always get resurrected, no matter what the infliction. And Corsham sees one scene in which she sprints off and scales a wall while in full dress and pregnant, not to mention that her carriage happens to be waiting within sight of her location for her to escape in. The different levels of reality in this story can sometimes feel jarring, although some might like this fantasy element.

In a similar vein to not being truly convinced by the figure of Child, I don’t feel the phrase ‘He knows’ that echoes through the novel and which is printed on the cover actually holds that much weight for the reader in the end. It turns out that a lot of people ‘know’ things about others—a lot of the plot is about revealing who knows what—so this specific ‘He knows’ doesn’t work as a powerful line for me.

Telling when it should be showing

While the quality of the writing in Daughters of Night is undoubtedly good overall, there is one key fundamental flaw that consistently appears, and overcoming this could really tighten up Shepherd-Robinson’s writing. It is something that needs to be learned by all writers, but I think the mastery of which is very difficult, and that is the principle of: show, don’t tell.

There are many instances in Daughters of Night in which the characters experience or say something and this is then followed by an explanation to the reader as to how the action or speech makes the character feel. In fiction writing, there shouldn’t generally be regular explanation of how a character feels if the action or the speech adequately infers that it provokes that feeling. If a writer is having to explain feelings to the reader all the time, it suggests that, as Louise Harnby writes in Editing Fiction at Sentence Level: ‘telling without texture is in play’. One should refer to Harnby’s book for some great examples of how this works (or doesn’t work) in practice.

Overly clever

One other point that can inadvertently act as a flaw as well as a strength is what comes through as Shepherd-Robinson’s intellect. Daughters of Night has regular references to antiquity and some utterances of Latin. To some extent, these inclusions are a marker of the time the novel is set in, and such references might at times be necessary. For example, it could seem odd if when paintings representing figures from Greek mythology are presented in the story, some comment about what the figures or titles represented were never to be mentioned. However, I personally find what I’d call ‘scholarly nods’ over-used, a bit hard to follow, and often a distractor from the main plot. There’s also an inconsistent feeling in that some parts of the plot can feel highly intellectual while other parts are quite simplistic.

Proofreading

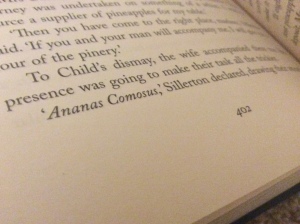

On a proofreading note, the book has been very thoroughly checked. However, there was this one horticultural reference in which I noticed an error. Can you spot it, too?

Overall, despite the flaws, this is an impressive work, and it will interest anyone who is interested in crime thrillers and historical fiction. Shepherd-Robinson’s next novel will surely likewise be another good read, although I fear that it might be prone to some of the same issues highlighted in this review. (I say that purely based on both of the first two books having exactly the same issues.) Maybe a beta reader could help!